How I spent two decades tracking down the creators of a 1987 USENET game and learned modern packaging tools in the process.

The Discovery: A Digital Time Capsule from 1987

Picture this: October 26, 1987. The Berlin Wall still stands, the World Wide Web is just text, and software is distributed through USENET newsgroups in text files split across multiple posts. On that day, Edward Barlow posted something special to comp.sources.games:

«conquest – middle earth multi-player game, Part01/05»

That’s how Ed Barlow announced it at the time, before quickly changed the name to Conquer.

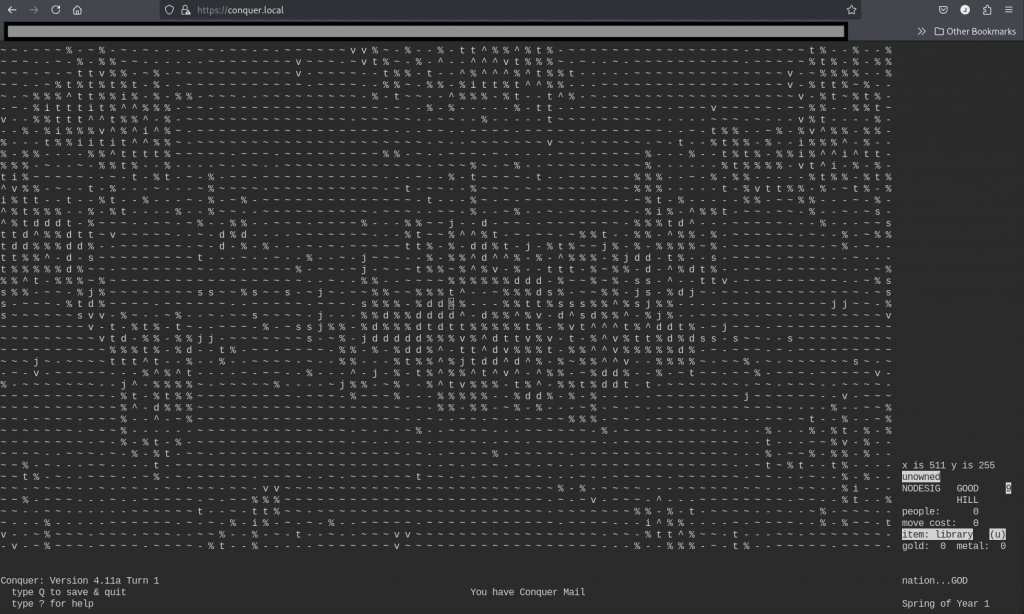

This was Conquer – a sophisticated multi-player strategy game that would influence countless others. Players controlled nations in Middle Earth, managing resources, armies, magic systems, and diplomatic relations. What made it remarkable wasn’t just the gameplay, but how it was built and distributed in an era when «open source» wasn’t even a term yet.

Chapter 0: University Days.

It was during these days, in the middle of the 90s, that my fellow students and I spent hours experimenting with terminals in the Computer Unix Labs, USENET, links, news, msgs, and of course: conquer. That game was a gem that required to be the leader of a country, and with a map representing as characters each player could control their elven kingdom, orcish empire, or human armies to fight each other while controlling all the details of the economy.

But by 2006, this piece of computing history was trapped in legal limbo.

Chapter 1: The Quest Begins (2006)

As a university student in Spain in the early ’90s, I’d encountered Conquer in the Unix labs. Fast forward to 2006, and I realized this pioneering game was at risk of being lost forever. The source code existed, scattered across ancient USENET archives, but its licensing was unclear – typical of the «post it and see what happens» era of early internet software distribution.

I started what I thought would be a simple project: get permission from the original authors to relicense the code under GPL so it could be properly preserved and packaged for modern Linux distributions.

Simple, right?

Chapter 2: Digital Detective Work

Finding Edward Barlow and Adam Bryant in 2006 was like archaeological work. Email addresses from the 1980s were long dead. USENET posts provided few clues. I scoured old university directories, googled fragments of names, and followed digital breadcrumbs across decades-old forums.

The breakthrough came through pure persistence and a bit of luck. After months of searching, I managed to contact Ed Barlow. His response was refreshingly casual: «Yes i delegated it all to adam aeons ago. Im easy on it all…. copyleft didnt exist when i wrote it and it was all for fun so…»

But there was a catch – I needed permission from Adam Bryant too, and he seemed to have vanished into the digital ether.

Chapter 3: The Long Wait (2006-2011)

I documented everything on the Debian Legal mailing lists, created a GNU Savannah task (#5945), and even wrote blog posts hoping Adam would find them. The legal experts were clear: I needed explicit written permission from both copyright holders.

Years passed. The project stalled.

Then, on February 23, 2011, something magical happened. My phone buzzed with a contact form submission:

«I heard news of the request to release the code. I grant permission to release the code under GPL.» – Adam Bryant

He had found one of my articles online and reached out on his own.

Chapter 4: The Plot Twist – Version 5 Emerges (2025)

Fast forward to 2025, and Stephen Smoogen contacts me about my relicesing efforts in 2006 and how he was particularly interested in reviving: Conquer Version 5 – a complete rewrite by Adam with advanced features like automatic data conversion, enhanced stability, and sophisticated administrative tools. This wasn’t just an update; it was a complete reimagining of the game.

But V5 had a different legal history. In the ’90s, there had been commercial arrangements. Would Adam agree to GPL this version too?

His response: «I have no issues with applying a new GPL license to Version 5 as well.»

Chapter 5: The Missing Piece – PostScript Magic

Just when I thought the story was complete, I discovered another contributor: MaF (Martin Forssen), who had created PostScript utilities for generating printable game maps – a crucial feature in the pre-GUI era when players needed physical printouts to strategize.

Tracking down MaF in 2025 led me to his new email. His response: «Oh, that was a long time ago. But yes, that was me. And I have no problem with relicensing it to GPL.»

Richard Caley: More Than Just a Legal Footnote

But not all searches end with an answer. Some end with silence.

My investigation of Richard Caley followed the same digital breadcrumbs. I traced him to the University of Edinburgh, where he worked on speech synthesis. I found his technical contributions to FreeBSD. But the trail went cold around 2005.

Then I found him – not in a USENET archive, but on the front page of his own website, preserved exactly as he left it in web.archive.org.

«Richard Caley suffered a fatal heart attack on the 22nd of April, 2005. He was only 41, but had been an undiagnosed diabetic, probably for some considerable time. His web pages remain as he left them.»

Reading those words felt different from finding a historical record. This wasn’t archival research – this was walking into someone’s house years after they’d gone and finding a note on the table.

The page continued:

«Over and above his tremendous ability with computers and programming, Richard had a keen mind and knowledge of an extraordinary range of topics, both of which he used in frequent contributions to on-line discussions. Despite his unique approach to speling, his prolific contributions to various news group debates informed and amused many over the years.»

The «Caleyisms» – The Man Behind the Code

And then I discovered his «Caleyisms» – a curated collection of his most brilliant USENET responses that revealed not just a programmer, but a person:

What’s a shell suit?

«Oil company executive.»

How do you prepare for a pyroclastic flow hitting Edinburgh?

«Hang 1000 battered Mars bars on strings and stand back?»

On his book addiction:

«I never got the hang of libraries, they keep wanting the things back and get upset when they need a crowbar to force it out of my hands.»

His humor was dry, intelligent, and uniquely British. In technical discussions, he could be brutally precise:

«Lack of proper punctuation, spacing, line breaks, capitalisation etc. is like bad handwriting, it doesn’t make it impossible to read what was written, just harder. But you probably write in green crayon anyway.»

A Digital Office Preserved

Exploring his preserved website felt like walking through his digital office. The directory structure revealed his passions: FreeBSD how-tos, POVRAY experiments, wallpaper images, technical projects. His self-deprecating humor shone through in his «About» section:

«Thankfully I don’t have a photograph to inflict on you. Just use the picture of Iman Bowie to the left and then imagine someone who looks exactly the opposite in every possible way. This probably explains why she is married to David Bowie and I’m not.»

Here was a complete person – technical director at Interactive Information Ltd, speech synthesis researcher, FreeBSD enthusiast, Kate Bush fan, and a wit who brightened countless online discussions.

The legal reality was harsh: Richard’s contributions to Conquer couldn’t be relicensed. The university couldn’t help contact heirs due to privacy laws.

His friends had preserved his memory with a simple ASCII tribute at the end of his page:

^_^

(O O)

\_/@@\

\\~~/

~~

- RJC RIP

In the Conquer project documentation, Richard Caley isn’t remembered as a «problem case» or «unlicensable code.» He’s honored as the vibrant person he was – the brilliant mind behind the «Caleyisms,» the researcher who contributed to speech synthesis, the FreeBSD advocate, and the witty participant in early online communities whose words continue to amuse and inform, decades after he wrote them.

Chapter 6: Modern Renaissance – Enter GitHub, CICD and Modern Distributions

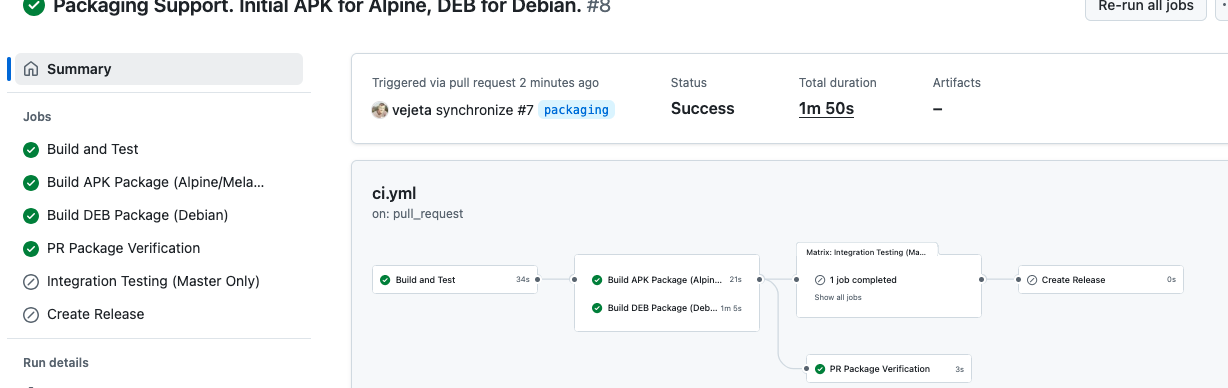

Here’s where the story gets really interesting. While working on preserving these Unix classics, I decided to learn modern packaging techniques. I chose to implement both APK (Alpine Linux) and Debian packaging for the games.

For APK packages, I used Melange – a sophisticated build system that creates provenance-tracked, reproducible packages for the Wolfi «undistro». The irony? I discovered this tool when some friend started to work for the company that created it.

Chapter 7: The Technical Journey: From USENET to Modern CI/CD

The transformation has been remarkable:

1987 Original:

- Distributed as split USENET posts

- Manual compilation with system-specific Makefiles

- No version control or automated testing

2025 Revival:

# Modern CI/CD with GitHub Actions

- name: Build APK package

run: melange build conquer.yaml

- name: Build Debian package

run: dpkg-buildpackage -b

Key Modern Additions:

- GPLv3 relicensing

- Make building system modernization

- C Codebase partially updated to support modern ANSI C99 specification

- Debian packaging

- APK packaging with Melange

You can see the complete transformation in the repositories:

- Conquer v4 – The original classic

- Conquer v5 – The advanced rewrite

Original Conquer v4 code, by Ed Barlow and Adam Bryant

(Conquer running in docker container alongside Apache, Curses to WebSockets output thanks to ttyd. Now we can play through the web!)

Conquer Version 5 – The evolution of the classical Conquer, by Adam Bryant

Chapter 8: The Human Element: Why This Matters

This isn’t just about preserving old games – it’s about preserving the story of computing itself. Ed Barlow and Adam Bryant were pioneers who built sophisticated multiplayer experiences when most people had never heard of the internet. They distributed software through USENET because that’s what you did – you shared cool things with the community.

Martin Forssen’s PostScript utilities represent the ingenuity of early developers who solved problems with whatever tools were available. Want to visualize your game state? Write a PostScript generator!

The 20-year relicensing effort demonstrates something crucial about open source: it’s not just about code, it’s about community and continuity. Every time someone maintains a legacy project, documents its history, or tracks down long-lost contributors, they’re weaving the threads that connect computing’s past to its future.

Lessons for Modern Developers

- Document everything: Those casual USENET posts became crucial legal evidence decades later

- License clearly: Ed’s comment that «copyleft didnt exist when i wrote it» highlights how licensing landscapes evolve

- Community matters: Adam found my articles because the community was talking about preservation

- Technical debt is temporal: What seems like legacy tech today might be tomorrow’s archaeological treasure

- Modern tools can revive ancient code: Melange and modern CI/CD gave 1987 software a 2025 renaissance

The Continuing Story

Both Conquer games are now fully GPL v3 licensed and available with modern packaging. They represent not just playable software, but a complete case study in software archaeology, legal frameworks for preservation, and the evolution of development practices across four decades.

The next chapter? Teaching these classic strategy games to a new generation of developers and gamers, while demonstrating that proper legal frameworks and modern tooling can give any historical software a second life.

Sometimes the best way to learn cutting-edge technology is by applying it to preserve computing history.

What historical software deserves preservation in your field? Have you ever traced the lineage of code back to its original creators?

#FreeSoftware #OpenSource #SoftwarePreservation #Unix #GNU #Linux #Packaging #Melange #TechHistory #GameDevelopment #Unix #USENET #GPL #FST #Debian #ncurses #terminal #shell

Read this article in Spanish / Lee este artículo en español:

https://vejeta.com/conquer-una-odisea-de-20-anos-en-arqueologia-digital/

This article was originally written in both English and Spanish, with additional insights and cultural context in the Spanish version.